Denis Nelthorpe and Carolyn Bond

Introduction

We will be adding more information to this page, but have decided to publish what we have written so far.

Here are some of our memories of financial counselling, the development of specialist consumer legal services and some of the cases and law reform campaigns. We hope this may be useful, particularly for people looking to find information that hasn’t previously been published. We were just two of the people involved in this social justice work over the years, and many people have contributed to the positive outcomes mentioned here.

Denis: I think you could say I had a challenging childhood. I was the second of five children. My mother was often unwell (I know now this was probably post-natal depression), our father sometimes struggled to bring in enough income, and he died when I was 15. While I didn’t excel at school (the Christian Brothers suggested to my mother that I leave school after year 10 and work in a bank) I wanted to be a lawyer.

In the late 60s, Perry Mason was a popular show on TV, where the lawyer always proved that the defendant he represented was innocent. I was attracted by the idea of justice – one positive thing that I can probably thank my Catholic upbringing for.

I was accepted into law at Monash University, but my mother didn’t have the money to pay the fees, which had to be paid up-front in 1971. A great-aunt offered to pay that first year of fees, and by the end of the year Whitlam had won the election meaning that my education would be free. I was also eligible for a student allowance. However, after a year of travelling 3 or 4 hours each day between Strathmore and Monash University (often hitchhiking), I used the allowance to pay for accommodation in the Halls of Residence. Holiday work, including, in a mattress factory and a phone book distributor, allowed me to pay for food and other expenses.

Quite naively, I’d never thought of doing law because of the money I could earn. I was surprised that many of my fellow students seemed less interested in the concept of justice.

I wasn’t quite sure what I thought justice meant at the time. I wasn’t political but would have chosen the Democratic Labor Party if asked. While the DLP was generally right wing, it was a Catholic breakaway from the Labor Party.

At that time, university offered a lot of extra-curricular opportunities, and I became involved in a group called Social Involvement (SIN). Members of this group networked with various residential homes – children’s homes, aged care, disability services (including Kew Cottages), visiting individuals, or taking them on outings. I started visiting boys at Hillside Boys Home in Jells Park. While group and family homes were being established elsewhere, those who weren’t deemed suitable for some reason often ended up at Hillside. SIN needed many more members, as we wanted to have every child/resident to match up with a student. I became President of SIN and managed to recruit dozens of new students.

I was shocked by what I saw at the boys’ home I visited. While my family home had not been ideal, there were no women on staff, some boys were quite young and punishments could be harsh – and many of these boys’ backgrounds were horrendous. How could the Government allow this?

I became the president of SIN, and managed to expand the membership and the range of places we visited. It was through this group that I met some of the friends I still have today – Gary Sullivan, Pam Williams, Cathy Andison, Alison Maynard, Wendy Singotta, John Hannonn Gerry Naughtin and Peter Naughtin. Gary, Alison and Wendy went on to work as lawyers in CLCs.

Monash was a hive of student activisim. It was the time of the Vietnam war. My brother Michael refused to register for the draft, and was hiding from the police.

I wasn’t at all radical, but two key things swung my politics to the left. Firstly, the Australian Government’s support of the US in the Vietnam war – specifically the bombing of Cambodia which hadn’t taken sides in the war, and seeing how poorly disadvantaged people were treated in government homes.

I took a 6-month break after 4.5 years of university – I only had 6 months to finish my law degree. I hitch-hiked to Queensland, spent some time at Nimbin (the alternative lifestyle there was a shock for a boy from a catholic school). I had the unfortunate experience of getting a much needed ride home on 11/11/75 with a truck driver who was crowing about the sacking of the Whitlam Government earlier that day.

At the time I finished 5.5 years at Monash, there were only three community legal centres in Victoria – Fitzroy Legal Service, Springvale Legal Service and West Heidelberg Legal Service. Working in community law was therefore not a realistic goal for most law students at the time.

I started my articles at a small law practice in St Albans in 1977. Conveyancing and family law – this didn’t feel much like the justice, and the principal I worked for was anything but enlightened.

Tenants’ Union (1977)

Denis: During my articles I became a night service volunteer at Springvale Legal Service. I also became a volunteer at the Tenants Union Legal Service. While based with the Brotherhood of St Laurence, the Legal Service operated under the auspices of Fitzroy Legal Service.

Through Mike Salvaris at the Tenants Union, I was introduced to a project “Practising Poverty Law”, auspiced by Fitzroy Legal Service. The idea was that a private practice could operate, where the income was used to provide free legal help to the disadvantaged people. I was engaged to do some the groundwork interviews, and the report was published by Sue Bothman and Rob Gordon,

The Tenants’ Union work was exciting, as we challenged – and took legal action against – landlords and agents. There was no tribunal for tenancy matters, so we had to issue in the Magistrates’ Court.

Mike was a barrister, who started the Tenants Union after meeting with other tenants in the block of units where he lived. Apparently, they didn’t know each other until they all came out the front to see a car accident and discussed the unfair practices of their landlord. Mike helped the group to fight the landlord in the Supreme Court, and a protest was held outside the landlord’s home.

Mike was approached by the Brotherhood of St Laurence, which at the time, provided assistance to public tenants but not private tenants. The Tenants Union (TU) – not ‘Tenants Victoria’ was born.

Alongside advice and representation to tenants, Mike drove significant reform work through a review of the archaic tenancy legislation, and TU volunteers subsequently helped with a lobbying campaign in support of the reforms.

As we later found when we worked on credit issues, industry can be taken by surprise when, for the first time, their practices are challenged. Greg Tucker (a volunteer law student at the time) decided to investigate some charges on leases offered by one large Real Estate Agent. (we think this may have been Williams and Co (now Williams Batters)). The relatively small amounts on each lease for stamp duty had not been payable for some time, giving the agent or landlord a large windfall across thousands of leases. The Agent was required to repay these funds to the tenants.

While legislation provided few rights to tenants, it was also difficult for landlords to navigate. In one case we defended one week’s notice given to a tenant by an eviction service (run by a man called Thomas Gidley). We argued that the 7 day notice should have been two weeks, and the Court agreed that 7 day notice was wrong. When the Gidley provided a 14-day notice, we argued in Court that 30 days should have been given, and again the notice was thrown out. Significant costs were awarded against the landlord, who may have not been aware until we sent the Court Sheriff to seize the landlord’s assets to cover the costs!

A private ‘community legal service’ (1978)

Denis: Once I finished articles, I tried to find a way that I could do something positive. With so few community legal jobs, I made contact with a number of community agencies. One was Taskforce (a large youth organisation in Prahran, run by Bill Manallack who later became CEO of Big Issue). I spoke with Maree Raftis from Carlton Community Health Centre who was working with refugees from Argentia, Chile and Peru, Bill Devemey who was running Employment Program for Unemployed Youth based in Kensington Flemington, and I met with the Catholic Family Welfare Bureau (CFWB) in Footscray. I think the introduction to CFWB was through the Sion nuns, who were based in Kensington, providing support to local people. All of those bodies were interested in a proposal for me to start a private practice in their organisation, and later on they all regularly referred clients. I set up a private practice based at the CFWB in Footscray in 1978. CFWB provided free rent, and I provided free legal help to their clients.

At the same time, discussion about the private practice model continued. With so few CLCs, this was considered as the only way to provide more assistance to disadvantaged people. Following publication of the report, Kevin Bell (another TU volunteer and later to become Supreme Court Judge) and I took the idea to the Western Region Council for Social Development.

Over a number years, fighting the legal profession, the proposal obtained seed funding from the Law Foundation – but not before Kevin and I had moved away from the project. Ultimately the project was the beginnings of the Footscray Community Legal Centre.

At that time (1978-1984) my main area of work was youth crime. Many of these clients were eligible for Legal Aid, when defending criminal matters. My income came from the occasional conveyancing matter, some clients who were able to pay for legal representation, and from Legal Aid which covered many of the criminal matters I ran. Initially the nuns contributed to my income to keep my head above water in those early days. As well as doing casework, I ran legal education talks at a number of youth organisations.

Consorting laws (1984)

Denis: I was not satisfied with simply providing legal services, but wanted to see reforms that would improve the lives of my clients and the community. My view was that the role of lawyers helping low income shouldn’t be to hold their hands while they politely lost due to an unjust law.

One effective action was to stop the police charging young people with the offence of consorting.

In 1983, it was common for police to book individuals for “consorting”. This meant they were associating with people who had been found guilty of criminal offences. The charge of consorting was only made out if a person had been booked a number of times (most cases involved 5 or more ‘bookings’) and generally clients pled guilty when faced with such a charge. In reality, this was a way for the police to harass or move on young people, often charging teens for being with friends – even siblings – who had any criminal history. In fact, the law dates back to Dickens’ time when it was created to deal with criminal gangs. It was time to challenge the laws and the application. My client was charged with consorting, and the police claimed he had been booked about 7 times. I briefed Lenny Hartnet, a barrister who I knew was prepared to take on a fight with the police. In the Footscray Magistrates’ Court, he demanded that the police prove every charge, requiring the police to bring more than 10 of their colleagues to the Court to give evidence. This involved the majority of police from the local area.

There is no defence to consorting (unless it can be proved the individual was not present) but the Magistrate wasn’t prepared to make a guilty finding. The Magistrate made the comment that the case raised the question about whether young people could have friends. I also had a media strategy. There were numerous media reports, including support for our case by a nun who was a probation officer.

I also engaged with state politicians on the issue. While we were successful in having the law abolished in the Lower House, the reform failed due to the National Party members in the Upper House opposing the change. I’m unaware of any consorting matters being taken to court in the following 20 years.

Introduction to credit and debt issues

When Carolyn started work as a financial counsellor in Footscray in 1981, I had my first experience dealing with credit and debt issues. The law didn’t help consumers very much, but we did what we could.

One of Carolyn’s clients was charged with malicious damage after he kicked and damaged the car of a person who served a court summons. When we examined the summons, it hadn’t been issued – so while it was on the right form, it wasn’t a legitimate court document. I defended this client in his criminal case, and it was probably helpful that I was able to argue that the ‘victim’ was in breach of the Unauthorised Documents Act (Vic) 1958.

Tenants Union (1978)

Carolyn: I grew up in Burwood in the Eastern suburbs of Melbourne. With 2 younger siblings my childhood was quite uneventful. I was quite rebellious as a teenager – I didn’t know anyone who had been to university and didn’t have ideas about my future. After getting through year 12, I enrolled in Business Studies in 1974 – but after 4 weeks I moved out of home and worked full time at a supermarket. I had an interest in ‘computers’, though not sure if I knew what that meant. After a few months I started in a clerical job at a computer bureau, spending the next 4 years working in computer services as a clerk and later a computer mainframe operator.

I was always interested in social issues and impressed by people on TV who advocated for social change issues, but had no contact with that realm personally. I was clearly looking for something because I recall during one of my holidays when I was about 20, volunteering at a neighbourhood service. When my landlord/agent kept all my bond in late 1977, it changed everything.

I called the Tenants’ Union for advice. All callers received a letter seeking volunteers, so I started spending a day a week on the phones during the day, as my computer work was shift work so most weeks I was free during the day. I went in one day a week, and met Kaye, Karen and Mike Salvaris. Phone advice was quite simple, most people didn’t want to go to court to recover their bonds, so I was often helping people write letters of demand.

I mentioned to Kay and Karen that my own agent hadn’t responded to my written demand. They then told me there was a legal service on Wednesday nights.

When I arrived on the Wednesday night there were many tenants waiting for help. Mike saw me and asked me to see the next clients in line. I teamed up with one of the law students and saw a number of clients. As things were winding up at the end of the night, I told Mike that I’d actually come in for legal help! So, I managed to get some legal advice from one of the lawyers (I think it was Geoff Bowyer) before we all went off to the pub for drinks.

Wow – I’d found my home! Over beers, people talked about tenancy cases, as well as other cases (probably just ones they were studying at uni!) – but I was so excited by it all.

I continued to volunteer at the Wednesday night legal service and sometimes on the advice phones during the day. In those days most lawyers and law students weren’t interested in volunteering at such a service – the belief was that it would not look good when you applied for a legal job, it may indicate you’re a bit of a trouble-maker! So, half the volunteers were people like me, or people studying economics or social work. “Bring in your friends” Mike would urge us.

Based in the Brotherhood of St. Laurence building in Brunswick Street, the Tenants Union had a few staff and volunteers providing phone advice during the day, and the volunteer legal service ran on Wednesday nights. Tenants Union was inspiring. While community legal services were defending clients against government or police, the Tenants Union was proactive in issuing action against agents and landlords.

Here is a 1978 episode of the Tenants’ Union program on 3CR, where I’m interviewed as a volunteer at 12.30.

There was no tenancy tribunal, so matters were heard in the Magistrates’ Court.

Many years later I was a member of the Legal Services Board (which regulates the practice of lawyers) so some of this makes me shudder now – but I wasn’t a lawyer and I was signing letters of demand on legal service letterhead (we did receive a complaint about that) and in one case personally serving the landlord on behalf of a tenant. Mike said “you live near that landlord, this is how you serve a summons” – and so I did!

Over the last 40 years, my work has focused on the power of casework – using legal cases or knowledge gained from casework to identify problems and get change. That really started with Mike and the Tenants Union, and I’m convinced that when casework and policy and campaigns work together, we can get good outcomes.

Community Committee for Tenancy Law Reform

Carolyn: A lot of work had been done, and the report had been released, and it was time to lobby for law reform. There was a roster set for all the volunteers, and who they were going to visit to tell them about the recommendations – councils, community organisations etc. So, I had to quickly get on top of the reforms required and why they were important, and I went to meet people from various community agencies to encourage them to support the reforms.

Tenants’ Union demo

Carolyn: At the end of one night of legal service, Mike announced we were going to show up on the Saturday at a large estate agent’s office “Williams and Co” with mops, buckets and brooms. W&C were notorious for keeping bonds, noting “cleaning” as the reason. I can’t recall the impact we had, but we walked into one of their larger offices and started cleaning to make our point. This was probably Denis’ and my first date!

I’d managed to get my mother to come to help out at TU on the Wednesday night because we needed a typist. One night we were asked to paste up posters (about Tenancy Week I think), and Mum drove while I jumped out and pasted the posters. Gee it was nerve wracking – and Mum had to clean the glue out of the car when she got home. “Don’t tell your Dad” she said.

Financial counselling (1981)

Carolyn: In 1981 Denis told me there was a job being advertised in Footscray for a financial counsellor, and he suggested I apply. His explanation was that I had experience suing landlords, and financial counselling was just the opposite! At the time financial counselling was very new. There were a handful of positions throughout Victoria, funded initially as part of a program designed to prevent children from going into care. There was no training, and no guidelines, so some took a conservative approach helping people to budget and enter into arrangements with creditors, some worked within the community to establish food co-ops or credit unions. I suspect that few people (if any) applied for the job, perhaps as there was only 5 months of guaranteed funding left! For some history of financial counselling in Victoria, see “Financial Counselling in Victoria: the first 40 years”, by James Degenhardt.

I struggled initially. To be honest I didn’t really know what I was supposed to be doing. Most clients had little money, they often had a number of debts and there were no consumer protection laws for credit. I also found that no legal services were providing advice about credit either – so there was nowhere to get legal help except to ask Denis, who at the time was solely doing youth crime.

Paul Bingham and Bev Kliger were two other financial counsellors based in North Melbourne and Coburg. Paul had finished his law degree but wasn’t admitted to practice. We talked about the need for legal help for our clients, and in 1982, we organised a meeting in our house, which Denis and I shared with Alison Maynard, who was still studying law. The three of us met with Bev and Paul, and Dick Gross came along. We decided to set up a legal service one night per week. The Consumer Credit Legal Service (CCLS) was born. Incorporated in April 1982, we had no funds at all, but Centre 56 (Now North & West Melbourne Neighbourhood Centre) gave us use of their building on a Wednesday night. Our main cost was postage, so we were grateful to obtain our first annual grant from Legal Aid for about $2,000, which paid for stamps.

From the start, interviews with clients were undertaken by a lawyer and a financial counsellor. The financial counsellors would often turn up with their clients who needed legal advice. None of our legal volunteers knew much about consumer credit law or the practices of the finance industry, but working together the lawyers and financial counsellors, we could often find solutions.

It’s hard to imagine now what finance companies could get away with in those days because consumers had no way to dispute their case. I invited one of my clients to see a lawyer with me. She had been approached at her front door by the man from Walton’s Credit, who asked if she’d like to take over the account of the neighbour who had disappeared. She agreed, thinking she’d have a credit account – not knowing she was signing up for a $4,000 debt! We were in time to defend the court summons, we found a lawyer to represent her free of charge and (unsurprisingly) she won her case.

In 1984 CCLS obtained funding for a co-ordinator, and employed Dick Gross, a lawyer who’d been a keen CCLS volunteer. We were also able to set up a small office in the Metal Workers Union building.

From the beginning, CCLS adopted a similar approach to that we had experienced at the Tenants Union Legal Service – challenging dodgy industry practices, and if the law couldn’t help, taking direct action. In those days credit was always obtained through shop-fronts, so it was common to make threats to return the goods and make a fuss, or to have a protest in the street.

CCLS objected to the licence of one finance company for egregious practices, using the current law the Money Lenders Act 1958, but was unsuccessful, which highlighted the limitations of the law.

While CCLS was the only specialist credit legal service in Australia, we started working closely with some interstate colleagues, initially from Redfern Legal Service.

Local Media

Carolyn: Jane Cafarella (who remains a close friend) was a journalist at the local paper, the Western Times, and I first met her when she wrote a short story about me being the new financial counsellor. Denis and I provided her with a few stories about dodgy companies, and she wrote a number of articles under the “Consumer Casebook” heading, including about Weight Care and Permanent Pantry.

Permanent Pantry

Carolyn: It didn’t take long for me to see that low income people were often the target of dodgy companies with exploitative marketing techniques. I started to see how vulnerable people were to salespeople who visited their homes – either cold-calling or invited. Permanent Pantry advertised in local papers, offering a freezer stocked with food for $x per week. The trick was that the weekly sum covered payment for the freezer and for the first lot of food, but customers had to pay cash for subsequent food orders. The general impression of the marketing was that the monthly payment would cover food and the freezer. Once the first lot of food ran out, the people who came in for help didn’t have the funds for the next food order, so just had a debt to Custom Credit for an expensive – empty – freezer.

I’m not sure that we had much impact on this scheme, but there was a story in the local paper and I recall meeting with Consumer Affairs Victoria staff about it.

Weight Care

Denis: Prior to the introduction of linked credit laws, lenders could not be held responsible for any loss caused by merchants they had relationships with.

The ANZ Bank had provided Weight Care with the facilities to sign customers up for new ANZ credit cards, which the company then charged for their weight loss program. However, the company went broke without providing the services, having signed up many of the customers to an ANZ card just days before they went into liquidation.

Weight Care had marketed their weight loss program in shopping centres, with people dressed as bunny rabbits handing out flyers. Half a dozen of the women who had lost money went with CCLS to the ground floor of ANZ head office, and demanded to see the manager. This received media coverage [Margaret Simons] and the ANZ released everyone at the protest from the debt. However, CCLS managed to get refunds for more people, as those clients helped by calling through the list of creditors to speak to other victims.

The publicity initiated by CCLS led to the Victorian Government deciding to proclaim the linked credit provisions of the new Victorian Credit Act urgently, and these were introduced about 6 months prior to the full Act. These allowed a consumer who suffered loss at the hands of a trader to seek compensation from the company that provided credit in certain circumstances.

Bills of Sale & the ‘Avco dump’

Carolyn and Denis: A significant action jointly by CCLS and financial counsellors, which had a national impact, was the “Avco Dump”. At the time, if a borrower had no collateral and/or low income, lenders took a mortgage (called a Bill of Sale) over all the borrower’s property, and listed items such as beds, vacuum cleaners and rugs. This provided a very strong incentive for borrowers to go without food – even risk homelessness – to protect these items. As one finance person said to a financial counsellor who was explaining that her clients couldn’t pay – “where is the baby going to sleep without a cot?”

We started to confront these more aggressively, with Denis and I (and possibly other financial counsellors) threatening (and at one point) dumping a house load of furniture at a finance company’s office in Footscray. Of course, the company didn’t want these goods and threatened to call the police! CCLS decided to do this in a bigger way.

In 1984, two financial counselling services in Geelong had three clients who couldn’t pay these debts. There was an organised march down the main street in Geelong, which ended up in a removal van unloading furniture into the office of AVCO Finance. All of the four TV stations covered it in their news, and in an interview the following week with the head of the Finance Conference (the peak body for the finance industry), he promised that no members of the body would sign up a Bill of Sale or repossess goods secured by a Bill of Sale.

Coverage of the protest, and the aftermath, is here.

By 1987 CCLS had been able to employ a casework lawyer (Paul Bingham) in addition to the co-ordinator position. When Dick Gross left that year, Denis replaced Dick as the co-ordinator.

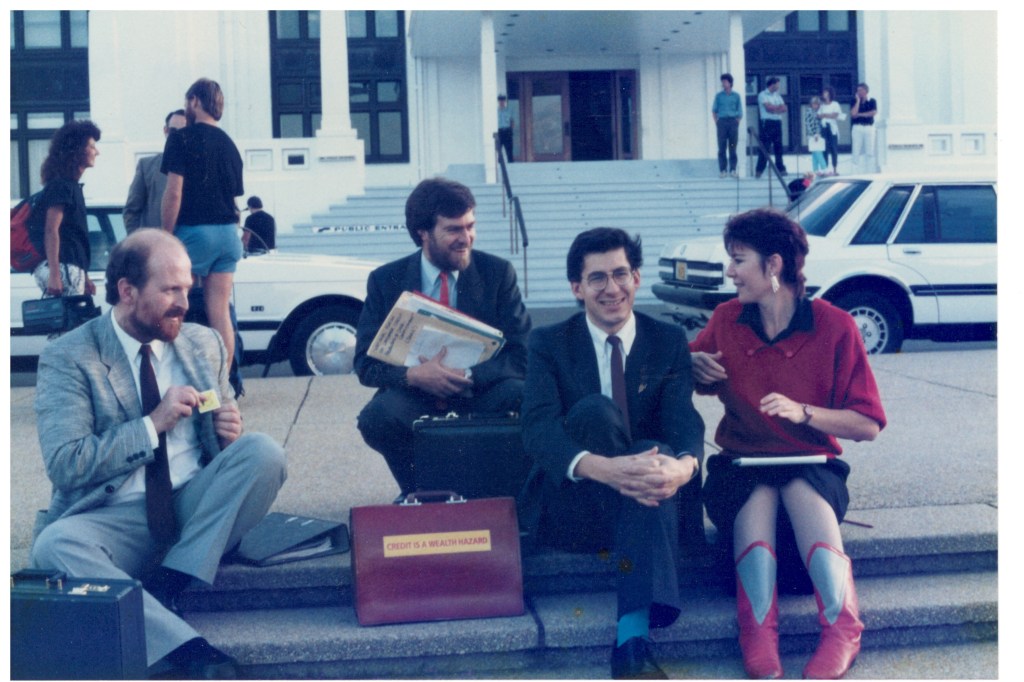

Credit licensing

Denis: Volunteering at CCLS, and supporting Carolyn with her financial counselling casework meant that I was gaining expertise in credit and debt laws fast.

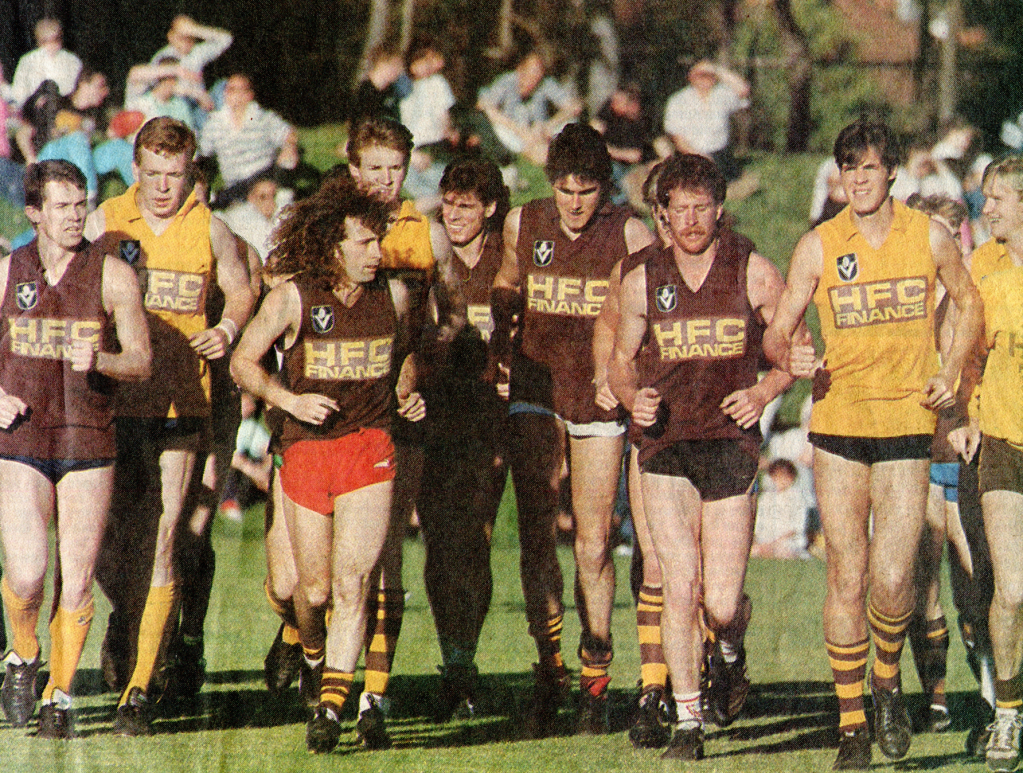

The new credit laws required [check credit act 1984 and credit administration act]. CCLS lodged objections to the licence of a number of smaller finance companies, we well as Household Finance, an American multi-national.

These objections relied solely on the issues arising from casework, so while CCLS had some cases, we relied on financial counsellors to provide the majority. This involved identifying the systemic issues from these cases, compiling the evidence and supporting clients to give evidence. While we only had a handful of cases when we lodged the objection, news about our objection led to many more. Consumer Affairs Victoria were also an objector, but I don’t recall them presenting any cases but took part so the Government department could have some input.

We were surprised when an objection to Pattersons Credit (a credit arm of a national furniture retailer) was successful following a three day hearing. We regarded the licensing objections as a means of highlighting inappropriate practices – it had not occurred to us that we might succeed in putting companies out of business.

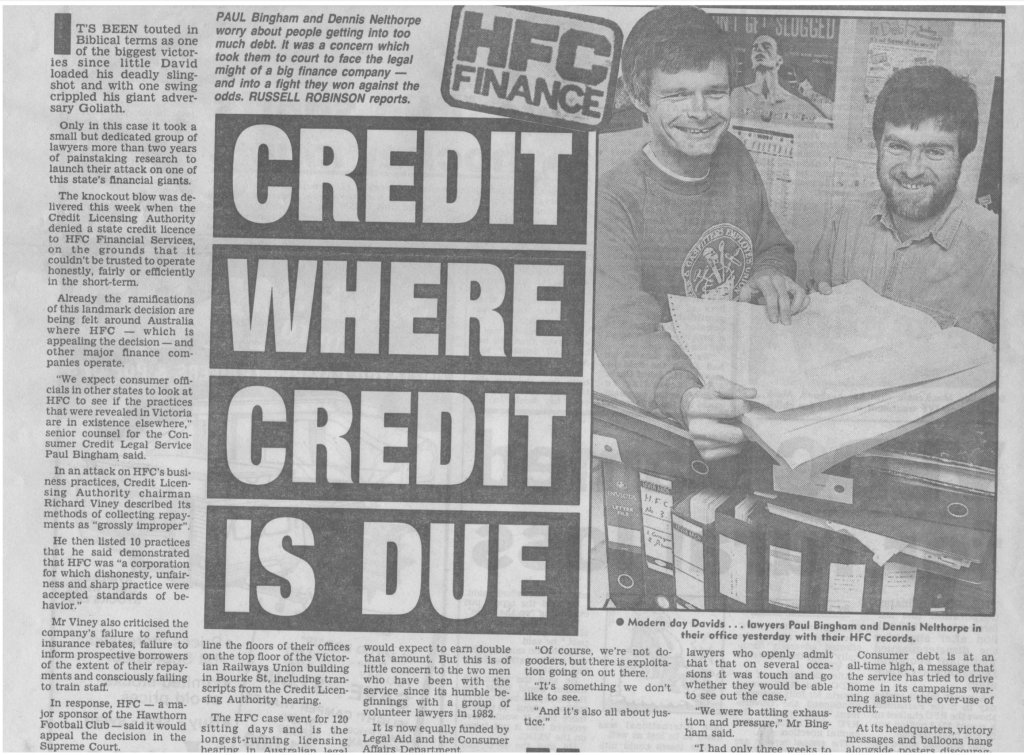

The hearing for Household Finance (HFC), which started in May 1988 and ran for over a year, was an incredible drain on our small service, which was staffed by 3 lawyers, 1 articled clerk, and 2 admin staff. HFC was a large multi-national company (and a major sponsor of the Hawthorn Football team at the time).

In those days there was no access to pro-bono lawyers or barristers. Paul Bingham and I were in the hearing during the day, and back to the office at night to prepare for the following day. This left one lawyer and an articled clerk to do all the other legal work. In addition to that, my first child was born during the first week of that hearing! Carolyn recalls at least one occasion where she was sitting up in bed feeding Hannah, while I was reading out to her the most recent hearing transcript.

The hearing before the Credit Licensing Authority ran for 12 months, and 18 months after the hearing started, the Authority decided not to grant HFC a licence. See further information here https://consumeraction.org.au/hfc-decision-1988/

HFC appealed the decision, and unfortunately this required a hearing de novo, meaning the case would be reheard, requiring all the evidence to be presented again. It’s unlikely that we could have managed that, but HFC were keen to find a way to settle too.

Interestingly, at this stage in the negotiations HFC stopped using their lawyers and hired a PR firm, which worked out better for both sides. We had to decide what we would seek from HFC in order to agree to withdraw our objection to their licence. Based on all their wrongdoing, we were able to identify the approximate financial loss to all their Victorian customers (not just those who had given evidence), and most of these consumers could be identified (for example because they had current loans or HFC had had a mortgage on their property). However, the Authority had found that HFC misled or coerced many consumers to purchase consumer credit insurance, in breach of the Act. While the Authority was satisfied of the percent who were likely not to have chosen to purchase it, totalling more than a $2 million gained unfairly by HFC, identifying those individual consumers wasn’t possible.

A Cy-pres settlement

Denis: I had visited US consumer organisations in 1987 with a grant from the Law Foundation. One of many things I learned was the use of cy pres in the US. Class actions were quite common on consumer issues, and inability to identify all those harmed was common. Courts in the US often made a cy pres order (or ‘next best thing’) so that the financial benefit obtained by the company would be donated to the type of organisation that might assist, or advocate for, the types of consumers who were harmed.

We proposed that advertisements invited any customers who believe they were mislead in their purchase of consumer credit insurance to apply for a refund (plus interest) , but that any funds that weren’t claimed by individuals be contributed to a fund to establish a consumer law centre. It was inappropriate for a number of reasons for those funds to be paid to CCLS, and HFC insisted that the funds be used for policy rather than casework. This $2.4 million was the initial funding that established the Consumer Law Centre in 1992.

Consumer Law Centre (1993)

A Board was established, and I was appointed the first CEO of Consumer Law Centre (CLC) in 1993.

Focusing on policy, CLC worked on regulation of energy, and produced reports such as “Why Women Pay More”. Without a litigation arm, I wanted some way that CLC could do casework, so we established Public Interest Law Clearing House (PILCH) – now Justice Connect. PILCH started with one staff member (Caitlen English) and worked within CLC for a few years. During that time, I was inspired by a John Grisham book called ‘The Street Lawyer’. Caitlin did the foundation work to establish the Homeless Law Legal Service, which eventually received funding and finally PILCH and HLLS established services separate to CLC.

I left CLC in 1998 and did some consulting work, including some AusAid projects which took me overseas. The most interesting of these was a project with the new Government in South Africa, which wanted to introduce consumer credit protections, and provide assistance to the many people in poverty who were trapped in high-cost debt. This resulted in two visits to South Africa, the final one with two Victorian financial counsellors (Jan Pentland and Dina Sayers), who shared our experience of financial counselling in Australia and provided training to community workers.

I did get to a point in 2005 where I wondered what I was going to do next. At that time it felt that CLCs were workplaces for younger people, or those who were early in their career. Should I do a masters and become an academic? – but that idea didn’t thrill me.

In 2006 I was asked by the Committee at Footscray CLC to act as a consultant and provide some advice about the direction of the service. I was also placed on the committee of another CLC which was facing some challenges, and Legal Aid had insisted on a replacement board. Shortly after that, I was asked if I could assist Werribee CLC, which also had some challenges.

I eventually became part-time CEO of both Footscray CLC and Werribee CLC. While at Footscray we developed the African Legal Service, Bring Your Bills Days (so we could identify financial issues without the client having to know the problem), and the Taxi Driver Legal Service (which focused on some of the unfair treatment of taxi drivers by insurers and taxi companies in relation to liability for accidental damage, and included me providing evidence to the Victorian Parliamentary Enquiry into the Taxi Industry).

In about 2015 Footscray CLC, Werribee CLC and Western Suburbs CLC merged to become WEstjustice. While the main office was in Werribee, we had offices in Footscray and Sunshine. I was CEO of WEstjustice from July 2015 until I retired in December 2019. However, I remained active on three CLC Boards, two of which I chaired.

Financial Counsellors’ Manual and training (1987)

Carolyn: Denis and I went overseas in 1985 – Dina Sayers stepped into my role as a financial counsellor while I was away. I didn’t stay I the role for long after I returned, and I was attracted to a training role that Financial Counsellors Association of Vic (FCAV) (subsequently FCRC and now Financial Counseling Victoria (FCV). There was no training for financial counsellors at the time, which meant that financial counsellors came from a range of backgrounds – including welfare work and accounting. There was also a lack of specificity about what the role of a financial counsellor was, and what knowledge and skills were required.

I started writing a manual for financial counsellors, based on my experience, consulting with others and legal input from CCLS lawyers. The manual was published in 1987, and by that time I had been running some training for financial counsellors for FCAV. An important part of the role was consulting with FCV members to develop some guidance about the role of a financial counsellor, and to start developing some basic ethics.

A key need was to clarify that a FC worked with and on behalf of the client, rather than acting as an intermediary between client and creditor. While this was the predominant approach in Victoria, there had been some in the field who saw their role as an intermediary rather than an advocate, and helping clients to budget and pay off debts – possibly driven in some cases driven by a belief that the client had a moral obligation to pay debt.

The manual was published in early 1987, and I’ve recently been reminded how this was used as a model for others states including Western Australia. In mid 1987 I left FCAV, in response to the difficulties caused by a dispute between CCLS and FCAV, the organisations Denis and I worked for. I found out shortly that I was pregnant, and I recall doing small pieces of work, including reception/administration for North Melbourne Legal Service. I think it was at that time I was first approached about teaching Financial Counselling at TAFE, an elective Kangan TAFE planned to offer community development students.

Hannah is born (May 1988)

Carolyn: This was a crazy time, as Hannah was born the same week that the Household licensing hearing started. Our son Paul was born 5 years later in 1993.

Between 1988 and 1995 I did a range of roles including locum financial counsellor at SouthPort Community Health, teaching a financial counselling subject which was an elective in the Kangan Community Development Diploma, writing some newspaper articles on consumer rights including a consumer column for the new Sunday Age, sitting on the Housing Guarantee Fund Appeals Committee and later co- writing the first Financial Counselling Diploma course for Kangan TAFE.

Consumer Credit Legal Service (1997)

Carolyn: In 1997, I was invited to apply for a new part-time policy role at CCLS.

It was over four years since Denis had left CCLS, and it had changed significantly – in particular the lawyers generally took a conservative approach and seemed uninterested in systemic reform work. The service focused on the legal practice cases and policy work was regarded as an ‘add on’. Credit Helpline was a telephone advice service which worked closely with CCLS, but was a separate entity. I attended weekly case intake meetings between the Helpline staff and CCLS lawyers, and I often raised the systemic issues that appeared to arise from these cases. This clearly irritated some people, including the new manager of the Helpline, who wrote to the CCLS manager suggesting that my issues were taking too much time and perhaps these should be discussed at another time.

While I contributed to a new report on the conduct of Avco finance, when a multi-state protest was planned, I was told by my boss that I could attend in work time, but I couldn’t identify that I was from CCLS. This was such a disappointing change.

This general attitude may have reflected somewhat of a development within the CLC sector, to become more ‘professional’. Sometimes this can mean a reluctance to undertake protests or campaigns that are regarded as radical. However, CCLS was probably at the extreme of this, with the lawyers differentiating CCLS from other CLCs by regularly referring to it as “a litigation practice” .

Despite this, I quite enjoyed this role, which included engaging closely with financial counsellors about the issues arising from their casework. I helped to develop some of the ‘How-to..” series which were basically guides for financial counsellors and caseworkers on topics such as cancelling consumer credit insurances, and dealing with mortgage debt issues – and once again debt collection practices kept arising as a consumer issue.

Management problems were arising at the service. Poor relationships between management and the Committee lead to the resignation of all but one Committee member. The direction of CCLS upset some of the financial counsellors, who had relied on CCLS to work with them to act on law reform and poor industry conduct, and to offer legal, and creative non-legal, solutions to help their clients.

Financial counsellors were behind the membership voting in a new committee that could change the direction of the service. Some instability followed with some tension between staff and the new committee.

In May 1999, the Co-ordinator gave notice, and the new committee asked me (via Murray Sayers and Jan Pentland I think) if I would be prepared to take the role of acting manager. I agreed, but the outgoing manager and some other staff were outraged. I wasn’t a lawyer, and they argued that it as vital that the manager role be filled by a lawyer, although I assumed that there was also some concern that I would support CCLS taking a stronger systemic advocacy role.

This was extremely uncomfortable, and I felt I couldn’t accept the role. Many of the staff signed a letter to the committee explaining why I shouldn’t be in the manager, including that I didn’t have the “experience, expertise and knowledge” to fill the role. It was clearly tempting to just walk away, however Denis gave me very good advice. While he was about to head overseas for 2 or 3 weeks, he suggested I ‘hang in there’ for a month, and then decide what to do.

The finance officer was popular with staff, and very active in challenging me, and complaining about me to other staff. He was also on the Committee – in the ‘staff rep’ position. He was rude to the new committee members who asked too many questions.

So, it may be no surprise that soon after I took on the role, I found that the finance officer had been stealing money from the service for the past two years. (A year later he received a suspended sentence). The discovery shocked everyone, but it probably provided the catalyst for some reflection and a change in organisation culture.

Collection House

I was initially alerted to problems with debt collector Collection House (CH)by Loretta Kreet from Legal Aid in Queensland, but financial counsellors and CCLS were seeing an increase in clients reporting CH’s poor conduct. While our principal lawyer had attended at least one meeting with a representative from Collection House, who assured her that the company had improved its practices, clients of CCLS, financial counsellors and interstate legal services, suggested there had been little change.

I decided to document our concerns, including case studies from financial counsellors and legal centres.

To be continued.

South Africa – AusAid funded work

In December 1997, Denis was invited to attend a meeting in Brussels with other consumer advocates from US, UK and Europe, to consider how the new South African Mandela government to make effective laws about exploitative credit. Denis made a strong point that without effective debt counselling (financial counselling as we know it), it would be difficult for any laws to be effective.

As a result, Denis was invited to visit South Africa the following year, to explore the establishment of debt counselling services there.

In 1999, Denis was asked to lead a study group from the South African Government 1999 to Australia, to look at the operation of financial counselling and consumer legal centres and meet with regulators in the lead up to the introduction of debt counselling in South Africa.

In September 2000, Denis was invited again to South Africa, and to bring two experienced financial counsellors from Australia, to provide training for community workers in financial counsellng. Denis brought financial counsellors Jan Pentland and Dina Sayers on this visit. He was also accompanied by our daughter Hannah, who was now 12 years old.

In 2001 or 2, Denis went to London for a discussion with the South African Government representatives to discuss competition and consumer laws. At this meeting, there were also consumer advocates and regulators from around the world.

Consumer Action Law Centre (2006)

Carolyn: In 2006, Consumer Credit Legal Service (CCLS) and Consumer Law Centre (CLC) merged to create the Consumer Action Law Centre.

CLC had been able to obtain funding for various projects over the years, and had managed to operate for about 12 years on these funds, combined with the original $2.4 million cy-pres settlement.

Victoria Legal Aid (VLA) proposed a merger of the two centres, which made a lot of sense to me. Both centres were too small, and the reason for them to be separate organisations was no longer there. Consumer Affairs Victoria and VLA agreed to commit to an initial three years funding for a new centre, and provide some funds for set-up costs.

I had two young children, and decided that I didn’t want to apply for the role of CEO for the new centre, but was happy to help progress the merger. At the time Catriona Lowe was on parental leave from the ACCC, and was working with a small project with Denis. I didn’t know Catriona that well, but she had worked at the CLC previously, so I knew her professionally.

Catriona came to visit Denis to discuss their project – and after they’d finished Catriona asked me what I intended to do. When I said I wasn’t going to apply for the Consumer Action CEO role, she said “How about a job share?”.

So we went about applying for the role. We know that the first offer was made to someone else – I understand the board being nervous about a job-share – but that person didn’t accept, and Catriona and I were offered a 6 day pw job-share, so that we would cross-over for one full day.

And didn’t we have some great staff to bring across from the two centres. For example, Gerard Brody, who later became CEO of Consumer Action after us, had started at CLC as a volunteer, and then a policy officer. I think the fact that I had history at CCLS, and Catriona had worked at CLC, was helpful in bringing both centres together.